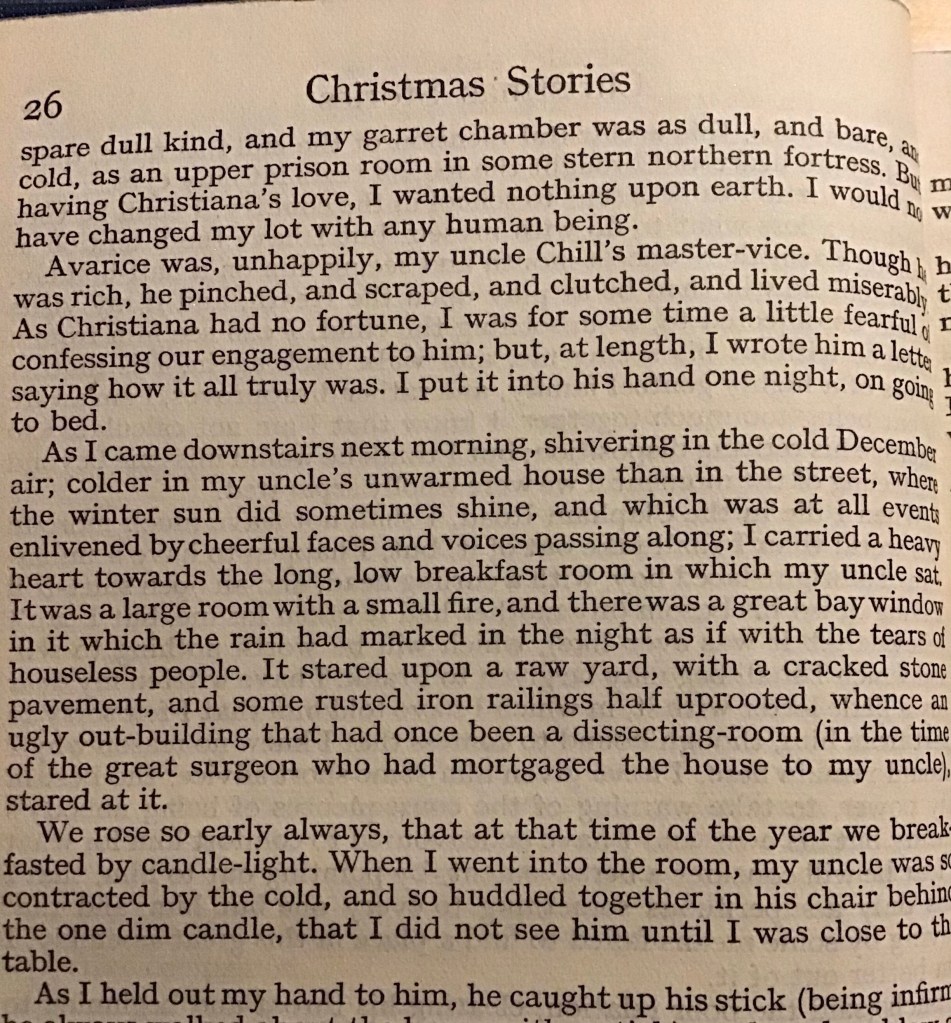

No small part of the success of ‘The Pickwick Papers’ published in 1837 was the inspired creation by Dickens of Samuel Weller, Pickwick’s servant and right-hand man and the creation of his father, coachman Toby Weller. It’s hard not to love this little picture of a group of respectable gentlemen inspired by Sam enjoying the ice on a freezing day.

So popular were the characters of Weller and his father that they were to appear again in ‘Master Humphrey’s Clock’ – a periodical published by Dickens between 1840 and 1841 and where he tried out the early chapters of both ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ and ‘Barnaby Rudge’ were tried out.

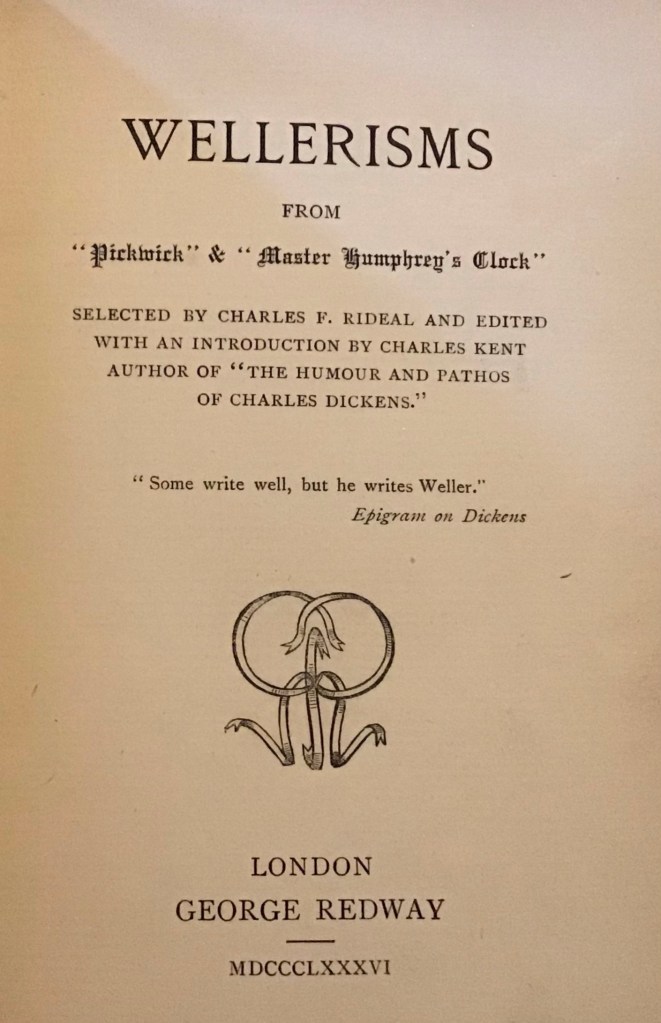

Even forty years later their popularity remained such that this volume of their sayings and exploits could still be successfully produced.