William Wycherley – his ‘little, tender, crazy Carcase.’

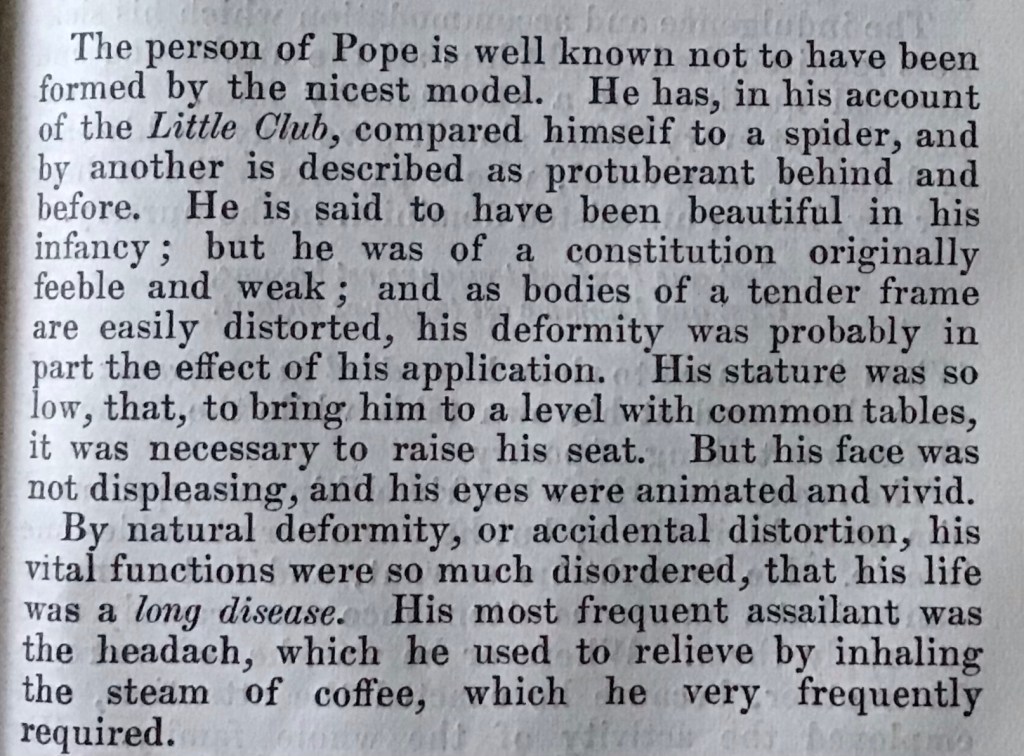

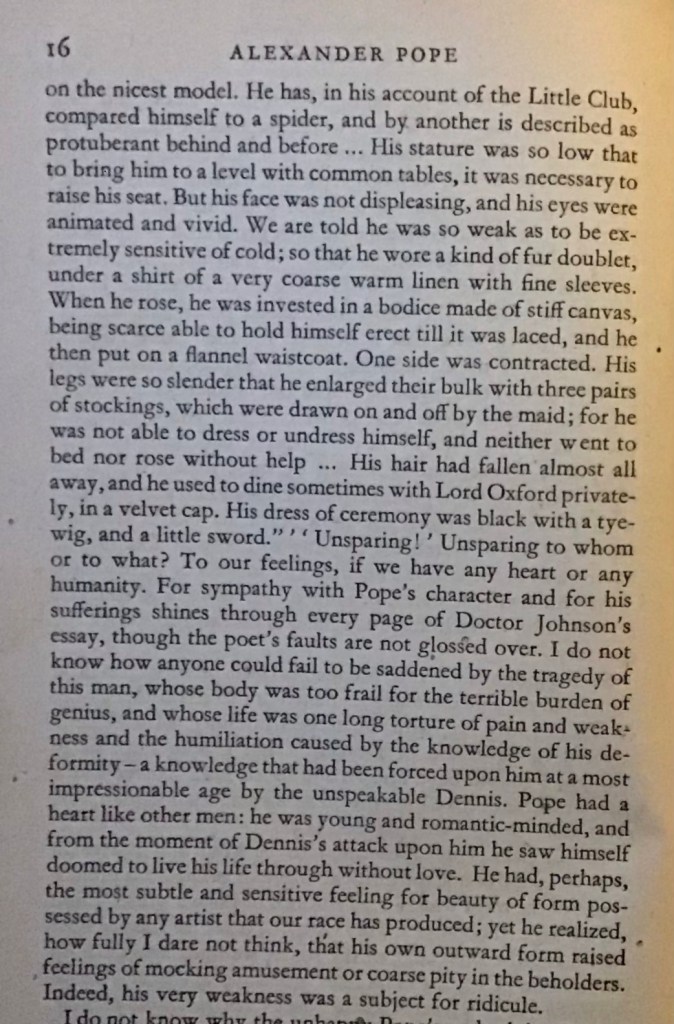

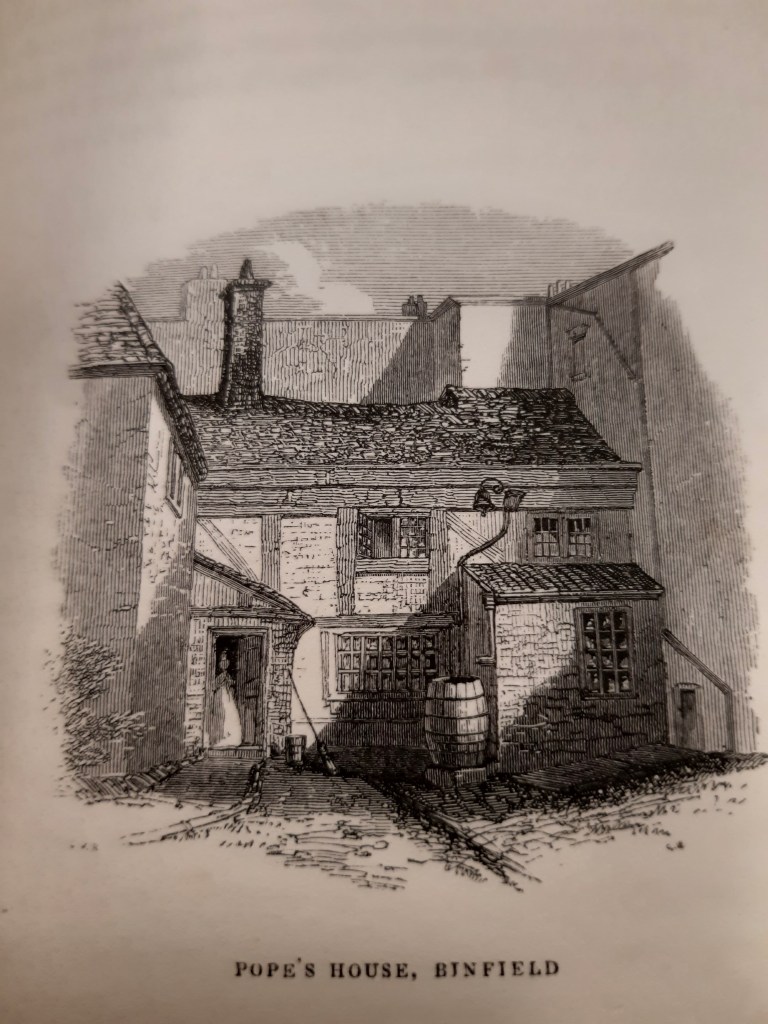

Portraits of Pope, paintings rather than, of course, the fearful caricatures which were made of him, seem carefully posed. Often, too, they suggest in his face the reality of living with pain. Careful poses may also be designed to conceal Pope’s considerable physical deformities. Pope became ill around the age of twelve and though he had periods of less restriction, he was chronically ill for the remainder of his life.

As Pope became ill, the hunt for an explanation began. Pope himself and others blamed incessant study while his older half-sister Magdalen blamed an incident in early childhood in which Pope was trampled by a ‘wild cow’ while at play. The cow ‘struck at him with her horns, tore off his hat, which was tied under his chin, wounded him in the throat, beat him down and trampled all over him.’

In fact, Pope had a tubercular illness causing a kyphoscoliosis – a double curvature of the spine. Sir Joshua Reynolds said he was about four feet, six inches high with a hunched back. The illness was at the time normally transmitted through milk and came to be known as Pott’s Disease after its identification by Dr Percival Pott (1714-88) without appreciating it was tubercular.

Throughout his life Pope suffered acutely with coughs and severe asthma in his later life. He grew increasingly lame and suffered a deterioration in his sight. He suffered headaches, stomach problems, piles, vomiting and urinary problems.

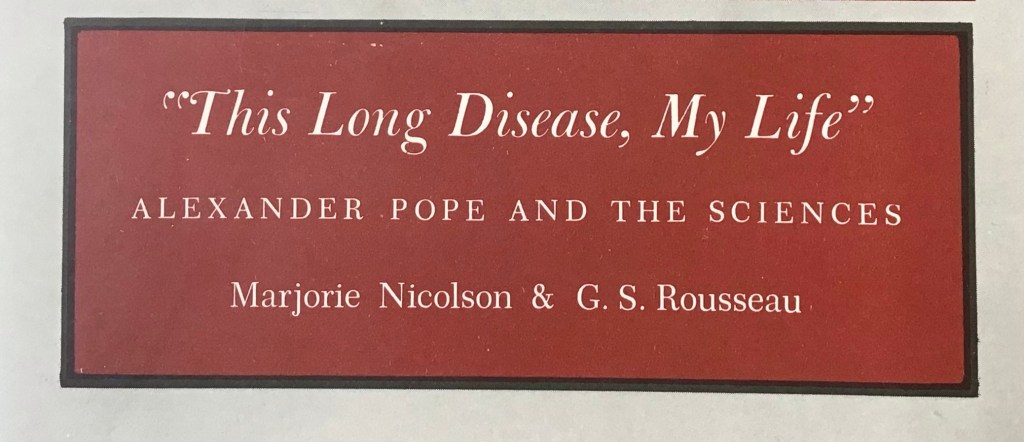

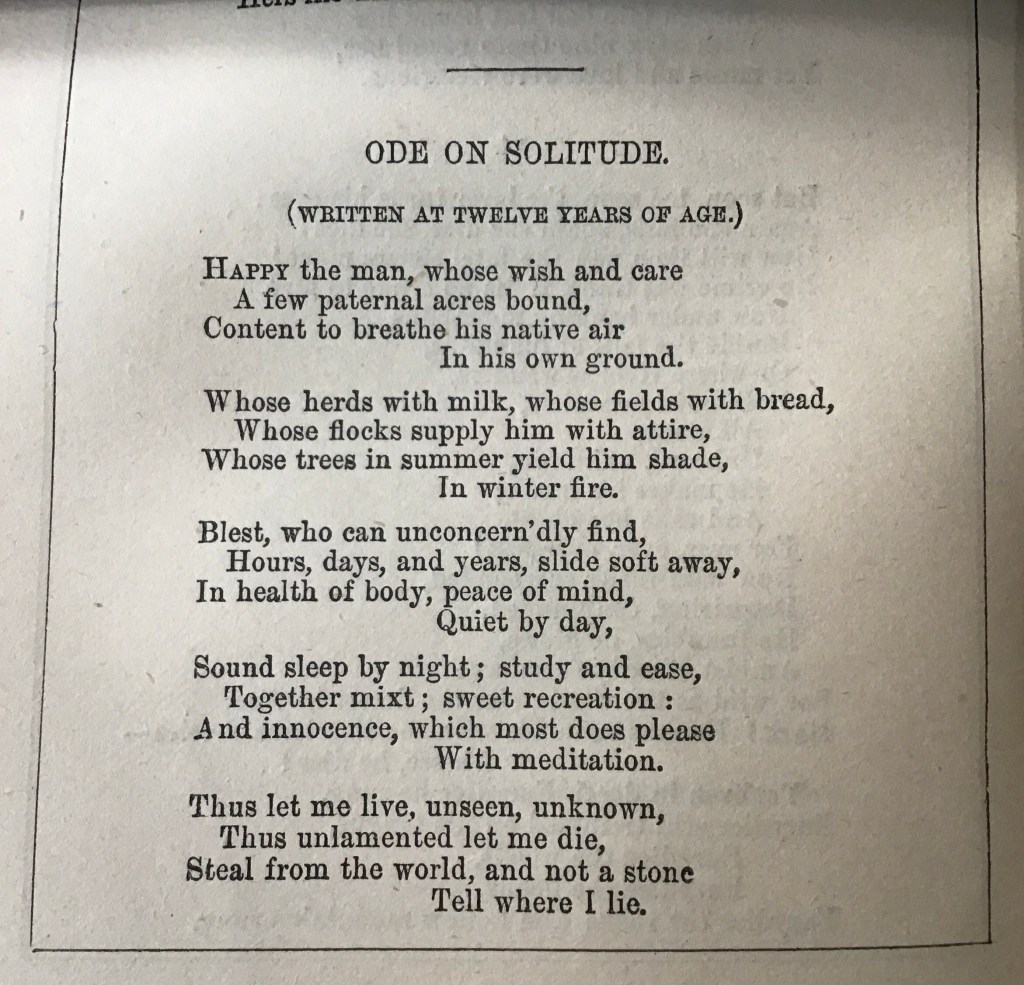

Yet his writings leap from the page with life and joy so much of the time and it’s hard not to see that as wondrous. More of Pope’s own words of his illness next time.