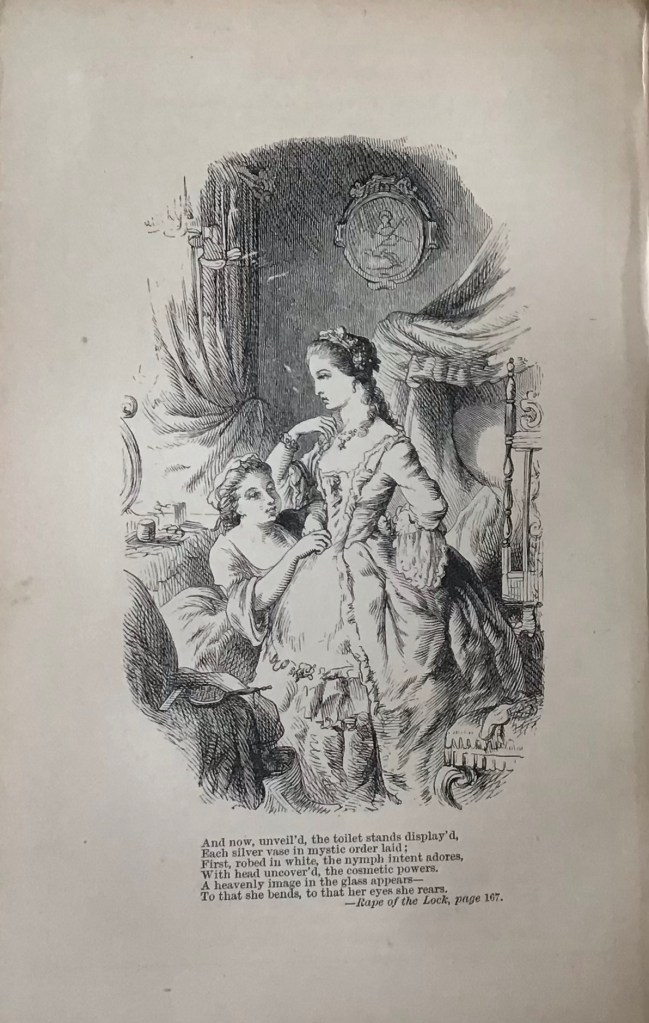

Of all the poems by Pope that I’ve read this is the one that I love the most. George I was crowned on October 20th 1714 so that places the event in time though the poem is dated to 1717. The young lady is Teresa Blount, who with her sister Martha were long-standing friends of Pope since his youth.

She went, to plain-work, and to purling brooks,

Old-fashion’d halls, dull aunts, and croaking rooks,

She went from Op’ra, park, assembly, play,

To morning walks, and pray’rs three hours a day;”

What I love about is how it captures the life of the young female members of the squirearchy in the eighteenth century so vividly. Pope’s teasing tone captures the immense tedium which must have been the day-to-day experience of many young women only occasionally interspersed with the excitement of London life.

What it reminds me of are two works which date from sixty years later but reflect exactly this world of the rural lower gentry. One is Goldsmith’s ‘She Stoops to Conquer’ of 1773 and the other is Sheridan’s ‘The School for Scandal’ of 1777. Consider this dialogue from ‘The School for Scandal’ in which Sir Peter Teazle confronts his young wife about her expensive lifestyle and reminds her of her previous rural upbringing.

How wonderful to get this poem in the post…