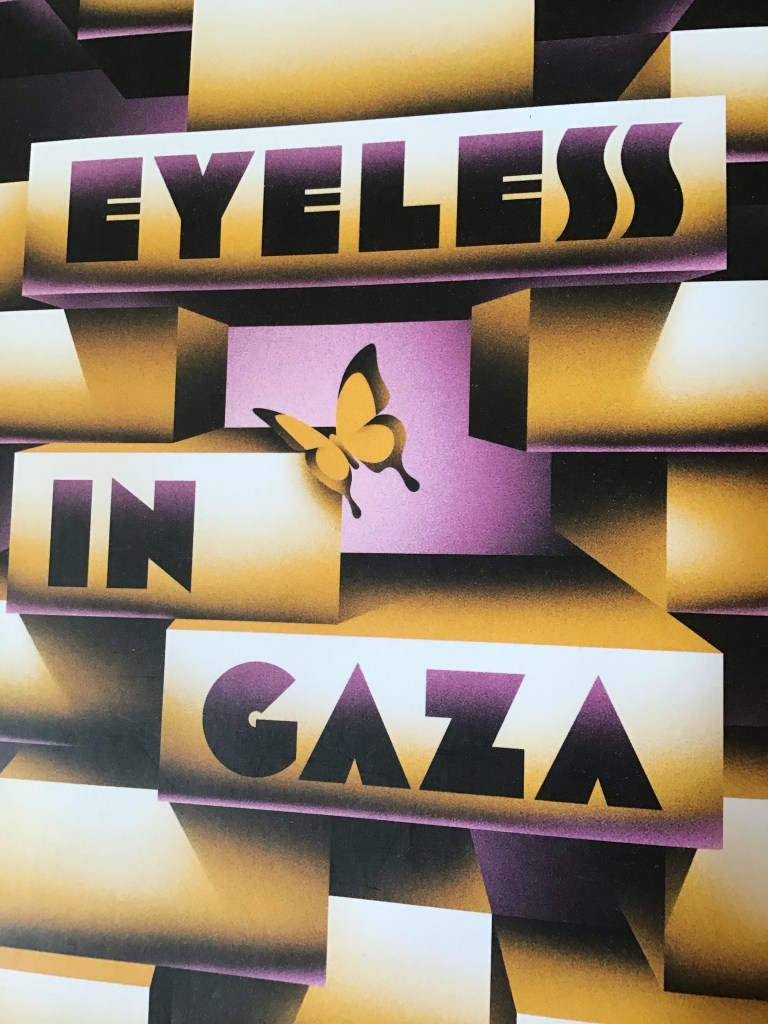

Sometimes you read something and immediately you know that you have read something important. This happened to me with Huxley’s ‘Eyeless in Gaza’ (1936). I’d chosen it as the second of my reads where the title was a quote from Milton. It’s again a quote from ‘Samson Agonistes’ – a poem which describes the final part of Samson’s life, blinded and a prisoner of the Philistines, ‘eyeless in Gaza at the mill with slaves.’

This post bothers me a little because I would hate to do such an extraordinary book any kind of injustice. Huxley builds in his account of the life his hero Anthony Beavis a vivid and powerful story about the different types of blindness and imprisonment which come from our education, our relationships and the competing philosophical systems which surround us.

The story moves backward and forward through the events of Anthony’s life. In that respect it reminded me a little of L.P. Hartley’s ‘The Go-Between’ perhaps in part because of the lasting impact of a suicide which is a part of both books.

For a book which is full of discussion of competing theories, political, religious and sociological as Beavis refines his ideas and develops his career as a sociologist, it is small, extraordinarily vivid episodes which impress so deeply. I found myself greatly moved by a description of Anthony taking his friend’s fiancée Joan to see a production of ‘Othello’. She has rarely been to the theatre and has only read the play and the description of the building of her emotional and physical responses to the reality of the play before her until she is overwhelmed is truly remarkable.

Anthony realises the pattern made in a life by these single events as he pieces them together in the very final pages of the book. He makes a unifying theory of these events and all he has read and believed as he prepares for a confrontation he knows awaits him.