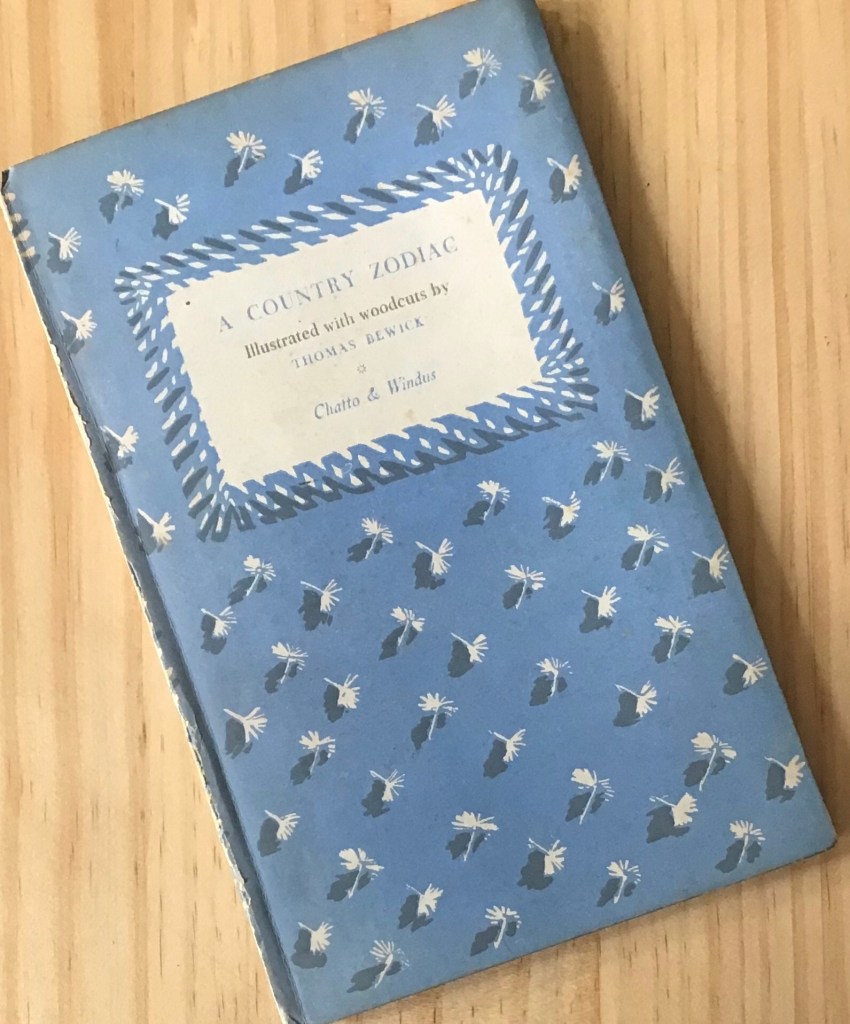

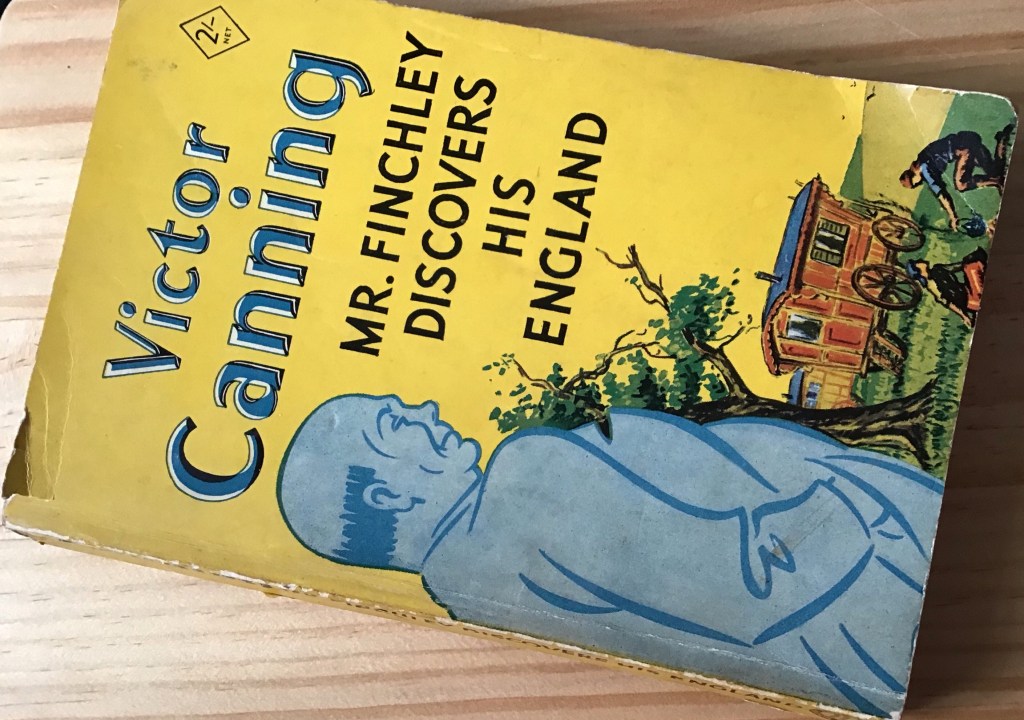

I picked up Canning’s book again because I vaguely remembered that as the book opens Mr Finchley, the hero of this the first of a series of books about his adventures, is about to begin a holiday in Margate. I should have been staying in Margate for a weekend a few weeks back so it struck a chord.

Canning’s book narrates the adventures of legal clerk Mr. Finchley as he’s about to undertake his first holiday for many years, three weeks in Margate. Missing his train by agreeing to mind a car and then being stolen along with the car, he begins a series of adventures which we can’t really call picaresque because of Mr Finchley’s great kindness and honesty throughout as he meets rogues, lost souls, great kindness, great adventures and a possible romance before returning home with Margate unvisited.

Like many books about holidays and travel more generally it is, of course, a book about self-discovery. Mr Finchley grows to understand the landscapes both of his life and the unexpected twists of his journey. Well worth a read.