Three months in to reading and thinking about Pope, I’ve been reflecting about the importance of place as I’ve considered the period of his life spent in his family home in Binfield and, importantly the landscapes that surrounded it. The impact of some of the works Pope produced while there – the Ode on Solitude, the Pastorals and a possible first version of Windsor Forest – their early assurance of Pope’s abilities combined with the vital energy of the landscapes reinforce the vision of the boy and young man in the landscape.

This may be why the physical places associated with Pope in this period stayed important. A look through guidebooks and recollections and reminiscences from Berkshire show how much the associations continued to matter. In his book ‘Favorite Haunts and Rural Studies; including Visits to Spots of Interest in the Vicinity of Windsor and Eton’ published in 1847, Edward Jesse captured why…

‘The fact may not have occurred to the notice of many persons, although it is curious and interesting, that from Windsor Castle, the residences of three of our greatest poets may be seen – those of Milton, Pope and Gray’.

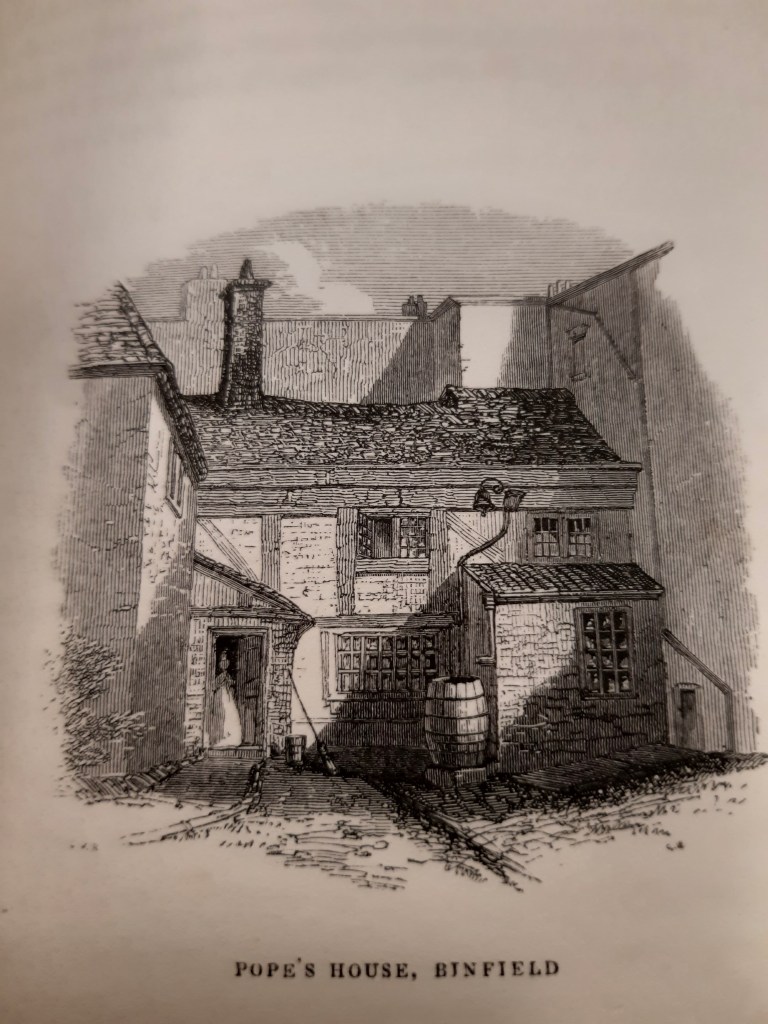

Jesse was disappointed that the much discussed tree with the words ‘Here Pope sung’ was no longer in existence though its former location was pointed out to him. He did, however, reach what remained of Pope’s family home at Binfield and his companion’s drawing was reproduced…

‘I will proceed to describe his house. There can be no doubt but that a great part of the original house has been pulled down, and upon the site of which the present mansion has been erected. Pope’s study, however still remains, and is now the housekeeper’s room, with some of the original offices still attached to it. It is a very small room on the ground floor, lighted by one window and at present rendered rather dark by a large screen of laurels. Such as it is, however, we viewed it with great interest, especially as the poet’s name is still honoured in the recollection of the inhabitants of the place.”

This seemed to be still the case in the 1920s when Allan Fea in his book ‘Where Traditions Linger: Being Rambles Through Remote England’ (1923). “The house, which has had half a dozen names since Pope’s time, is an ordinary looking Georgian erection, but within what is known as ‘Pope’s Study’ has been allowed to remain much in its original state.”

In the fourth edition of ‘The King’s England: Berkshire’ (1949) Arthur Mee captures the place again and also the fact that the Pope of Binfield was a very different figure than our idea of the man.

“The Scots firs a-row are still there, but of the house little but the memory remains. Here it was that the neighbours knew Pope, not as a sallow, bent little man, but as a fresh-complexioned boy with a voice in the choir ‘like a nightingale.’”

Latterly at Binfield, Pope began to suffer with the ill-health that was to dog his life. After his departure from Binfield as a young man his story grow more complex. Once established in the London literary scene, the sense of the man can be elusive.